Opening Note: This is one of the most defeating pieces I’ve ever sat down to write. I do not intend it as further demoralization in a sea of ubiquitous bad news and unprecedented unmooring. I intend it rather, as a modest addition to the beautiful calls issued by fellow educators in the past weeks to just Slow. Ourselves. Down. I am writing a series of quick autoethnographic snapshots of life as a graduate student-mother right now with the much more important intention of arguing that whatever I’m facing, students and workers with far less privilege and stability than I enjoy right now are facing much worse. At this time, we cannot prioritize academic rigor or “excellence,” whatever that means. We can at best attempt to provide some frameworks to help our students process what is happening (even though none of us really knows what is happening), or some modicum of distraction. Mostly though, we can model the urgency to choose care over “continuity.”

March 25, 2020Brown University announced yesterday that it would be freezing all hiring for the rest of this year, and for the 2020-2021 Fiscal Year. I feel like it’s only a matter of time before other schools follow suit. My plans for going on the job market next year are looking increasingly grim. And because of the bottle neck such a freeze will generate in all of academia, said plans will likely remain thwarted throughout the next year as well. Faced with shrinking job prospects in a market that already felt impossible, I’m experiencing a profound sense of disorientation as to what I should be spending my days doing.My life as a grad student mother before all this was very much defined by a house-of-cards balance between time and efficiency. But at least I had a relatively solid idea of what constituted an “efficient” use of my time (advancing on a dissertation chapter, applying for a grant, grading, prepping discussion section). But now I feel no anchor, no framework of rationality informing my decisions about what to do next. My husband and I are taking three-hour shifts to watch our thirteen-month old child. When I hand our baby-baton off to him and sit down at my desk, I stare at my computer screen not even knowing where to start. Should I be writing this piece or getting ahead a few weeks on recording my lectures because who knows what’s going to happen next? Should I go stock up on my anxiety medication because who knows what’s going to happen next (an uncertainty which, of course, is making me more anxious)? Should I call my parents in New York City yet again to yell at them to stop sitting on public benches during their beloved Central Park walks, because who knows what’s going to happen next? Should I say screw it all and just go spend time with my son and partner, because no matter what happens next, nothing else could ever matter more?

Despite my unmoored sense of what, exactly, constitutes an “efficient” use of time, I cannot stop obsessing about how best to squeeze a few more minutes out of an insufficient twenty-four hours I have in a day. If I put the baby in the bouncer in the bathroom and shower during my babycare shift, that’s fifteen minutes more to get stuff done during my working shift. If I do my run a little bit faster, I’ll have five-ten minutes to send an e-mail before the baby wakes up. If I type with one hand and nurse at the same time, maybe I can give my husband ten more minutes to work on his dissertation, and find some relief from this draining back and forth of feeling like every minute I take for myself is a minute robbed from him, and vice-versa. Maybe then, we won’t have a needless argument this evening about how he didn’t clean the dishes while I put the baby down – an argument that is about the dishes, but, as is the case with most marital spats, is also very much not about the dishes.

via GIPHY

In Facebook groups and Twitter threads across the internet professors send messages of care and concern for their students: This is not the time to be “productive,” they say, “this is the time to be at home with your loved ones and to tend to them.” But my sense of self-worth has been so intertwined with my academic “productivity” over my past 5.5 years as a grad student that the wires feel too crossed. Maybe this says something about me. But maybe it also says something about academia more broadly.And then as I start to feel sorry for myself, I snap back into the reality that all the problems and worries I listed above are privileged ones to be having. Yesterday, while walking my dog, I ran into a maintenance crew worker in the UCI graduate-student housing complex where I live. Having engaged in small chitchat with him on a regular basis since we moved in over five years ago, I asked him (from six feet away) how he felt about continuing to work through all of this. UCI had recommended that students living in dormitories and grad student housing return to their “permanent residences,” and could even break their lease with no penalty if they chose to do so. Such grace however, was not extended to UCI workers, who were now charged with cleaning the apartment units people left abruptly, and going in and out of units to do regular maintenance work. I see them riding in close contact to one another in the golf carts they use to get around the complex. I see them charged with cleaning the common space surfaces, some of which, more likely than not, carry the virus. We already have had a confirmed case within graduate student housing, and so it feels highly probable, that despite their use of gloves and masks, many of these workers will indeed contract the virus. I asked the worker if they were given an option for paid leave. He said they only gave him three weeks maximum. He told me he feared going home every night and potentially spreading the virus to his family, but what other choice did he have? Indignant, I told him that I’d try to mobilize some of the students involved in supporting the AFSCME local union that represents UCI workers. I spent the rest of my walk seething, plotting my next steps.

Then I got home. I panicked because I realized I had touched with my elbow a bunch of crosswalk buttons on my walk and I didn’t have any hand sanitizer and needed to get my son out of his stroller to get him upstairs. Once I got in the house, I didn’t know what to sanitize first. My own hands? My dog’s paws? My son’s jacket? Was I supposed to remove my outer layer of clothing before touching anything? Given that my son is at a stage where there is literally nothing that he does not want to put in his mouth, I look at my house like a minefield of biohazards. And in that flurry of uncertainty about the order of my sanitizing process, I forgot for the next few hours about my intentions to look into ways to support the workers. It wasn’t until later that night, (after putting the baby down, after counting our supply of diapers and wipes, after eating something, after wiping down all his toys for the millionth time today), in the fifteen minutes I sat down to watch TV before conking out entirely, that I remembered my conversation with the worker. I lazily Tweeted out some info, tagging key actors, and called it a day. What the fuck is wrong with me? All this, and I am someone who spends all her time writing about activists and the convictions that make them put everything on the line even when faced with uncertainties far more harrowing than those confronting my family right now.

I cannot remember a time in my life where it was more important to be actively working in solidarity with each other and yet my brain and body literally don’t feel like they can do more than keep my son and the rest of my family alive. My fear is that this virus will turn me into the sort of middle-class spectator I’ve always detested – one who fails to see how her own family’s wellbeing is intimately connected with the wellbeing of precisely those who are most vulnerable now. The only way I can think to avoid falling into this malaise is to refuse the impossible search for a semblance of normalcy and productivity in the ways that academia and capital have disciplined me to define them.

As is the case with most processes framed as “crises,” COVID-19 does not mark a rupture with an otherwise functional social fabric. Rather, it marks an exacerbated continuity. Yet because the nature of this virus so acutely highlights extant exploitations and inequities central to the operations of the University and the USA more broadly, we must seize upon this moment to refuse a framing of victory that prizes “getting things back to normal.” Yesterday I counted how many e-mails I received from UC Irvine in the course of a 24-hour period about “academic continuity” and how I can better deliver my courses remotely. Thirteen. I received thirteen e-mails on this one topic on one day. Only one day into the Spring quarter, I also have received several emails of another kind. They are filled with messages from undergraduates who are worrying about undocumented friends and family who don’t have access to healthcare. They are worrying that people like them will be first to be blamed when our woefully dysfunctional healthcare system inevitably collapses. They are worrying about just having lost their jobs and not being able to make rent or tuition. They are worrying about their dependence on public transportation that has now been shut down. They are worrying because they know they need to stock up on groceries but can’t, because doing so depended on a next paycheck that will now not come. They are worrying about a President on TV and Twitter, who by insisting on naming this pandemic the “Chinese Virus,” (or “Kung Flu” if you like your racism especially cheeky) is more or less sanctioning violence against people who look like them. I am exhausted, even in my capacity as a white-passing, relatively stably employed US citizen, with a newly naturalized citizen spouse, and a healthy baby with health care. How exhausted will our students be?

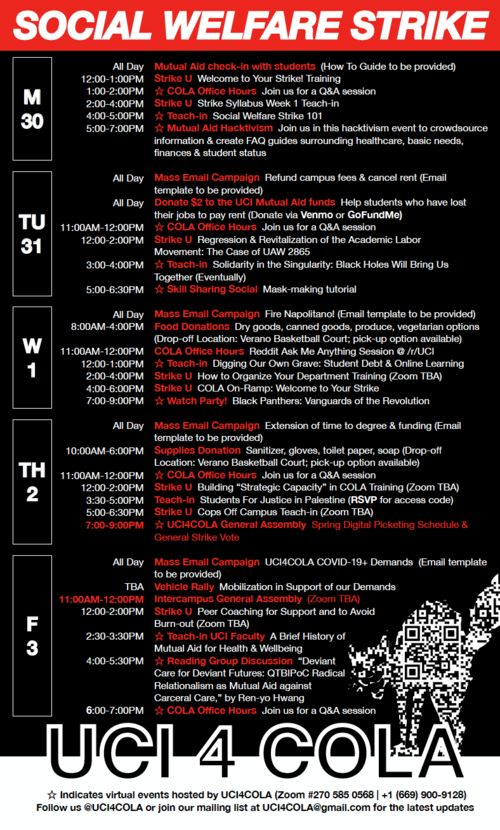

It is precisely because of this collective exhaustion that the COLA movement’s recent strategy pivot towards a Mutual Aid strike is so brilliant. Rather than engaging in a traditional work stoppage, workers in a mutual aid strike divert their labor towards supporting each other. It’s symbolic and material power is in its redefinition of “productivity” from accumulation to the redistribution of resources, and shifting frameworks of “safety” from the individual to the collective. UCI COLA organizer Semassa Boko writes beautifully, “Care has to be our number one priority in this moment, not continuity. Not work(ing for non-life saving institutions). We must slow down yet move with purpose.”My drive for continuity – to try to squeeze those extra fifteen minutes out of the day to send emails, to maintain academic productivity – is an instance of Berlantian “cruel optimism” at its finest. I am desperately working towards a return to a system that functions on my own exploitation, but more importantly on the workers and undergraduates who give the University its lifeblood. My exhaustion will cease when I refuse continuity and prioritize care.

Cite as: Rubio, Elizabeth Hanna. 2020. “What Do I Sanitize (or Do With My Life) First?: Refusing Continuity as a Grad Student Mother in the Era of the Coronavirus.” In “Pandemic Diaries,” Gabriela Manley, Bryan M. Dougan, and Carole McGranahan, eds., American Ethnologist website, 2 APRIL 2020. [https://americanethnologist.org/features/collections/pandemic-diaries/what-do-i-sanitize-or-do-with-my-life-first-refusing-continuity-as-a-grad-student-mother-in-the-era-of-the-coronavirus]

Elizabeth Hanna Rubio is an anthropology PhD candidate at the University of California at Irvine.